GPT-ing, fast and slow

Published:

GPT-ing, fast and slow

Disclaimer!

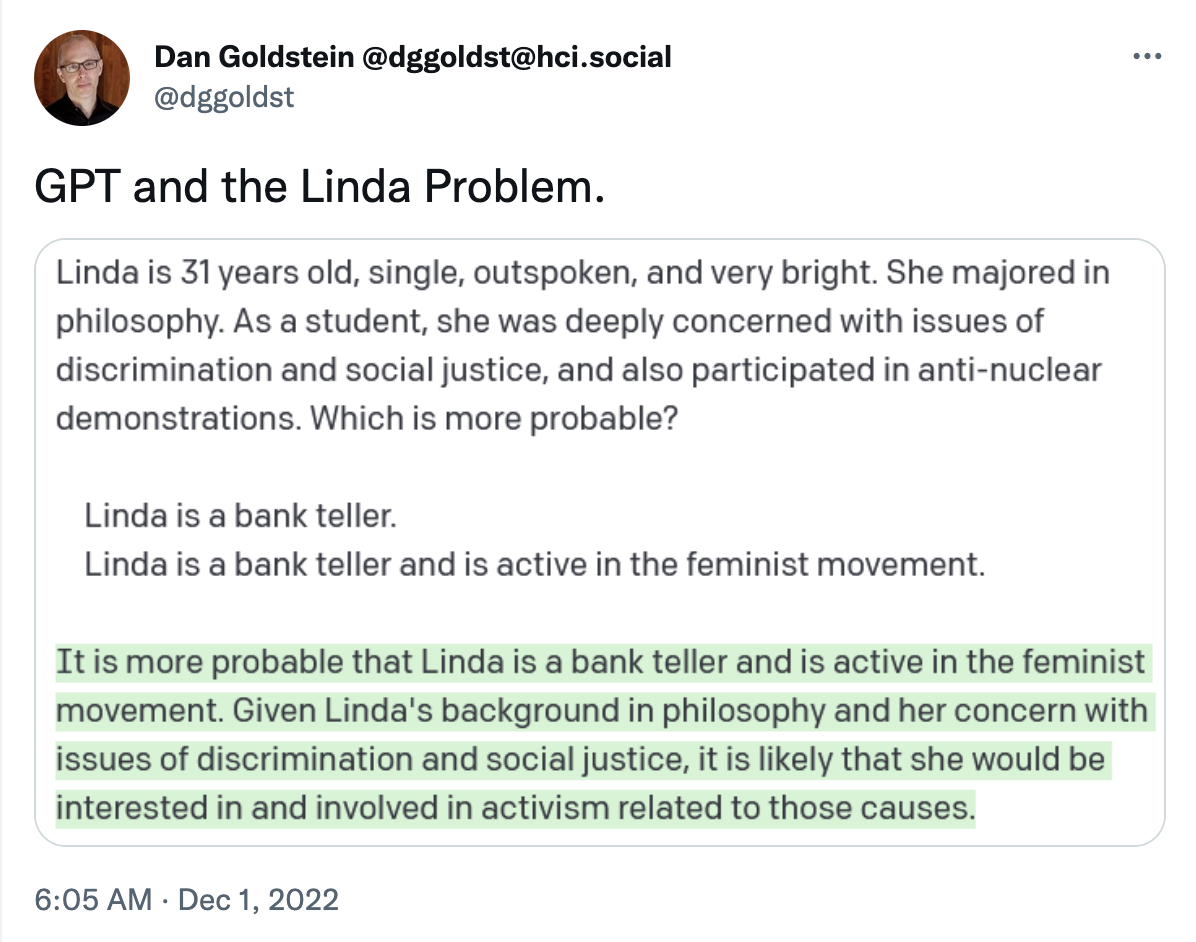

This idea is not solely mine!!! Last week, I saw a Tweet by Dan Goldstein, who gave GPT-3 the “Linda and the bank teller” riddle (Kahneman & Tversky, 1983). Somewhat surprisingly, it did not answer “rationally.”

I wanted to see what other classic heuristics GPT-3 does or does not fall for. Without further ado, here we go…

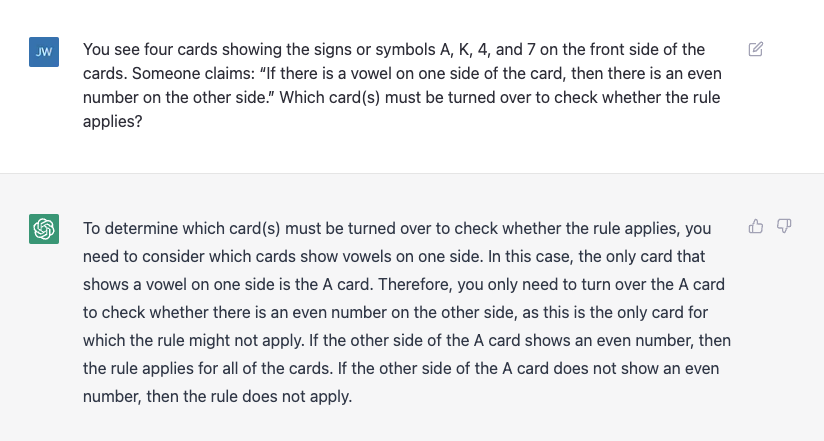

The Wason card selection task

This is a classic deductive reasoning problem, which is phrased as follows:

You see four cards showing the signs or symbols A, K, 4, and 7 on the front side of the cards. Someone claims: “If there is a vowel on one side of the card, then there is an even number on the other side.” Which card(s) must be turned over to check whether the rule applies?

The correct answer: The correct answer is A and 7. Most people can deduct that we must flip over A (in order to see if an even number is on the other side). However, what makes this riddle tricky is that we must also flip over 7. The contrapositive of “If there is a vowel on one side, there is an even number on the other side” is “If there is an ODD number on one side, there is a CONSONANT” on the other side. So we must ALSO check to see if 7 does NOT produce a vowel. This is the card that most people do not get. Although GPT-3 was trained on human speech, I hypothesized that the AI’s superior “problem-solving” skills would make it immune to this trap. But I was wrong!

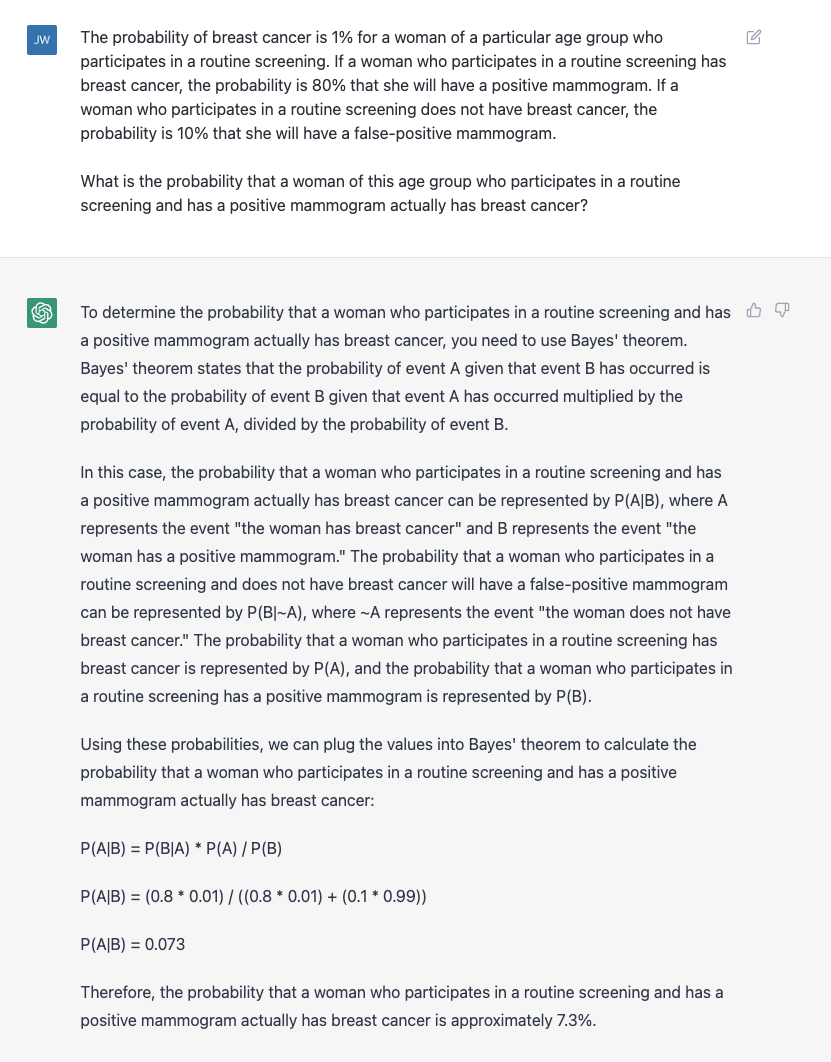

Bayesian reasoning

A common mistake people make is “flipping the conditional.” When presented with a conditional probability, such as the probability of breast cancer given a positive mammogram, people might use the probability of a positive mammogram given breast cancer (which will naturally be quite a bit higher). I gave GPT-3 this problem, and it solved it perfectly! Good job, little guy.

Empirical law of large numbers

In probability, there is a concept called the “law of large numbers”: In an experiment, the average of a large number of trials will be closer to the point truth than the average of a small number of trials. To a scientist, this might seem intuitive, but people who don’t do science for a living might not come to this conclusion so readily. The problem states:

A certain town is served by two hospitals. In the larger hospital, about 45 babies are born each day, and in the smaller hospital about 15 babies are born each day. As you know, about 50% of babies are assigned male at birth. However, the exact percentage varies from day to day. Sometimes it may be hier than 50%, sometimes lower. For a period of 1 year, each hospital recorded the days on which more than 60^ of the babies born were boys. Which hospital do you think recorded more days?

The correct answer is the smaller hospital. Using the law of large numbers, we say that the hospital with more “trials” (babies, in this case) is more likely to produce sex ratios closer to the ground truth. So, in conclusion the smaller hospital is more likely to have outlier days.

In previous research, most participants said that the two hospitals would have comparable numbers of days with more than 60% males (because the 50% average applies to both). GPT-3, however, gave a…uh, creatively wrong answer?

Framing effect

Kahneman and Tversky were also known for research about framing effects in decision making. A canonical example is that you are at the grocery store looking at different kinds of beef, and you notice two different brands, one of which says 85% lean and the other of which says 15% fat. While the fat content of these two brands is identical, when people are making decisions quickly, if they want to choose the “leaner” brand, they will go for the one with the label “85% lean.” To be clear, these heuristics are not necessarily bad: it’s actually very helpful to have a more “rapid” decision making system. There are just times when it leads to fun little cognitive illusions like this one.

I asked GPT-3 this question, and counter to my predictions, it totally fell for the framing effect! It even got SO SO CLOSE TO THE CORRECT ANSWER BUT STILL CHOSE WRONG.

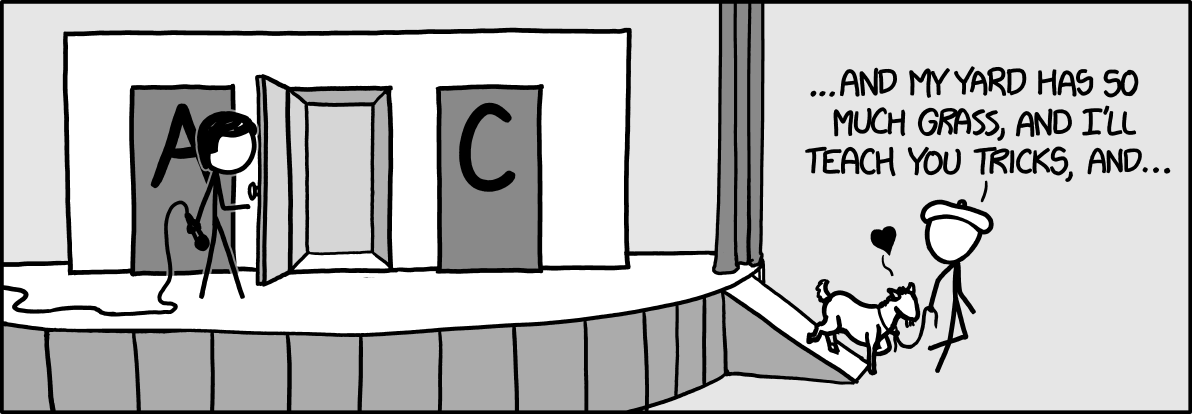

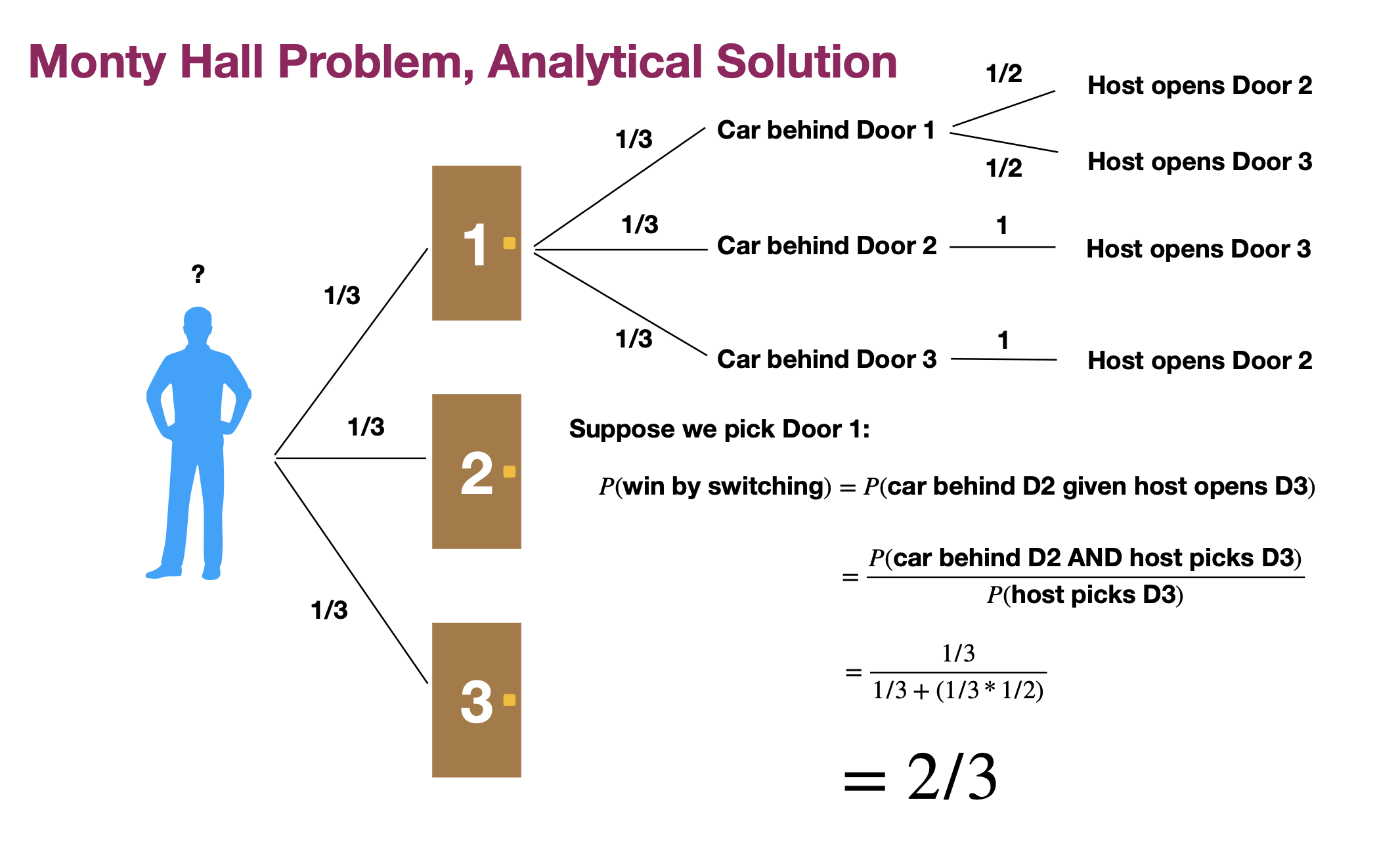

The Monty Hall problem

I was super stoked to ask GPT-3 the Monty Hall problem, which so frequently delights psychologists and statisticians alike. In this problem, you are on a game show where you are shown three doors. Behind two of the doors are goats (cute), and behind one of the doors is a car (fine). You first pick a door, and the host will then reveal one of the other two doors, which will always be a goat. The question, then, is whether or not you stick with your choice or switch. The intuitive answer is that it makes no difference: there are two doors remaining, so the probability of a car is 1/2. But the correct answer, using conditional probability, is that you should switch! In fact, if you switch, the probability of a car is 2/3. I won’t get too into the computations here, but there are all sorts of nice explanations on Wikipedia and beyond. Here’s a little diagram I made for a stats class once…

Interestingly enough, GPT-3 correctly guessed that switching is the way to go but miscalculated the probability of winning a car given switching.

This example (along with the law of large numbers example) is a cool instance of GPT-3 making an error but a different kind of error than humans would make.

And I’ll leave you with a cute XKCD comic.